From Icons to Interfaces

How religious icons and ChatGPT both connect us to another world

If you have visited some of the great cathedrals of Western Europe, then you may have experienced the feeling of leaving behind the noise and pace of the city and entering what feels like another world. The stones, the stained glass, and the majesty that surrounds the altar are all designed to help parishioners leave behind the things of this world and connect to the divine.

I had a similar feeling recently while visiting a church much closer to home, a Greek Orthodox church built in 19791. While it has the feeling of the late 1970s United States on the outside, on the inside you would think you had been transported hundreds of years into the past and thousands of miles eastward. Unlike even some of those cathedrals, the church is dominated by images, or icons. The eye is almost overwhelmed; it can be hard to know where to fix your gaze. Your attention is drawn to the icons, and whatever may have been occupying your thoughts before you entered is suddenly lost.

The reason for my visit was to experience for myself what it is like to have my mind unconsciously drawn toward another world. I was trying to better understand an argument that Ivan Illich makes in the radio series The Corruption of Christianity. In the third episode of the series2, he claims that a misinterpretation of the Church’s teaching on icons is the ultimate source of the disembodied nature of existence in the modern age. I spend a lot of time thinking and writing about the digital nature of our lives, but even I was skeptical of this claim from Illich. How could these ancient icons have anything to do with our current lives, so focused on screens and the potential of artificial general intelligence? Yet my visit and some further consideration have convinced me that there is a connection between those icons and our world, a connection that points to how we should approach the use of large language models and their god-like powers.

Illich begins his argument with the Hebrew scripture’s clear prohibition against creating images for the purpose of worship. “Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image,”3 as the second commandment says. This command helped to create an attitude against the creation of images of any kind, not just those to be worshipped. This was the environment in which the first Christians lived their lives. Yet with the coming of Jesus, “the image of the invisible God,”4 they were put in a position to reevaluate these assumptions. If Jesus himself was an image of God, did that mean that other images could be created? If so, of who or what? Church leaders eventually allowed the creation of images, or icons in Greek, of the saints and Jesus himself. Yet this was not without controversy, and during the Second Council of Nicaea in 787, the question of icons was a major focus. Did the second commandment apply only to images of false gods, or had the Church erred in creating these icons?

According to the council, the Church had not erred.

To summarize, we declare that we defend free from any innovations all the written and unwritten ecclesiastical traditions that have been entrusted to us. One of these is the production of representational art; this is quite in harmony with the history of the spread of the gospel, as it provides confirmation that the becoming man of the Word of God was real and not just imaginary, and as it brings us a similar benefit.5

The creation and use of icons continues to this day, as I experienced in my local Orthodox church. Yet this is where the “corruption” that Illich is focused on becomes evident. He argues that while Jesus’ embodiment did change the previous paradigm of the renouncement of images, the Church began to take this approval of images in an incorrect direction.

In the Eastern Church, icons are viewed as instruments to help people connect with an alternate reality through prayer. They are the threshold between the two realities; the image on the icon is a “prototype” of the actual reality in heaven, which it helps connect its user to. Again, in the words of the council:

Indeed, the honour paid to an image traverses it, reaching the model, and he who venerates the image, venerates the person represented in that image.6

Icons point people to the true reality behind the icon, where God and the saints dwell and hear your prayers.

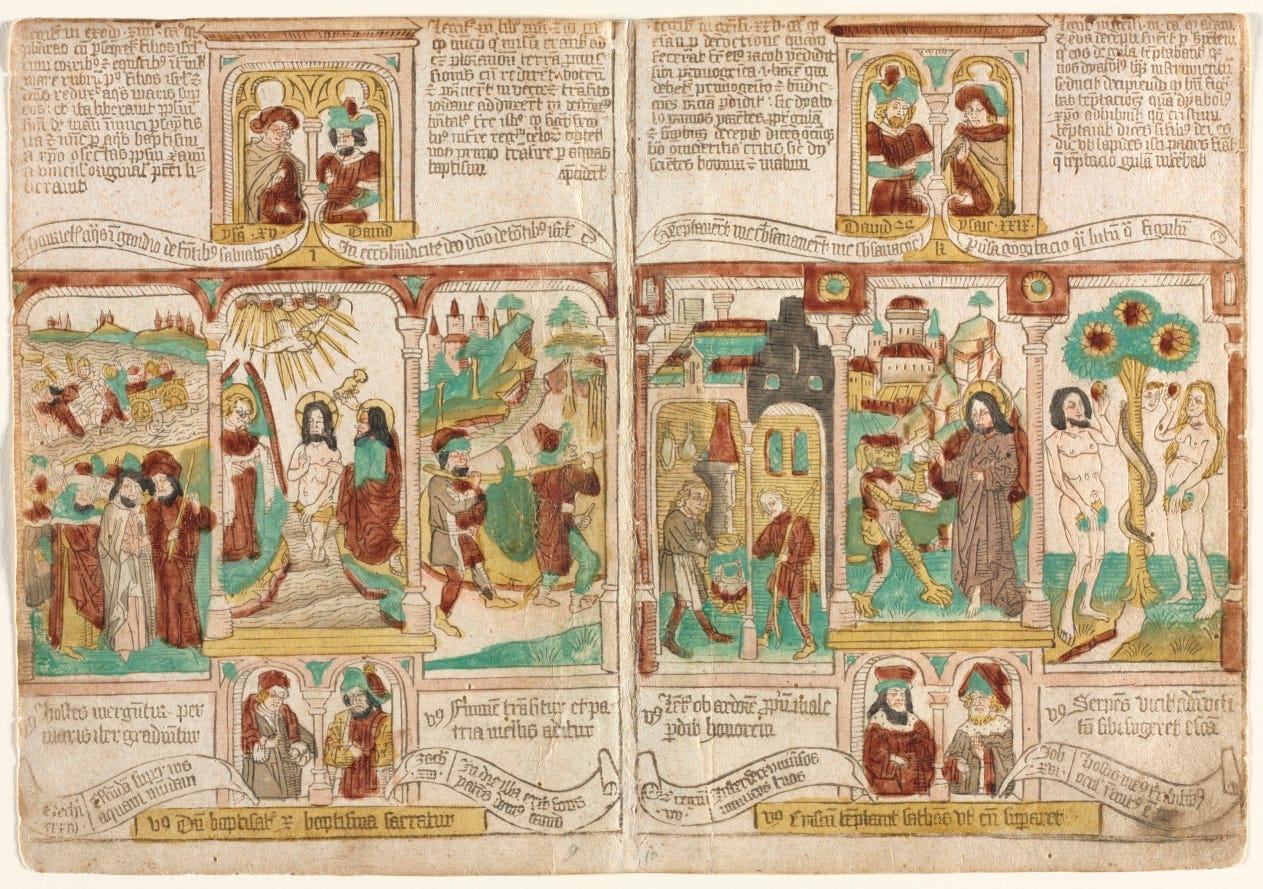

But the Western Church began to use images for other purposes, starting with the use of illustrations alongside scripture. This practice was expanded to paintings and stained glass in churches depicting scenes from the Bible. The goal was not to aid believers by connecting them to the divine in prayer but to aid them in understanding the scriptures. Parishioners, it was thought, would better understand and remember the scriptures if they were made more concrete, frozen in an image for all to see. But this concreteness also subtly shaped their understanding of the scriptures, recreating them in the image of medieval Europeans, not first-century Jews. Instead of pointing toward a heavenly reality, they resembled reality here on earth.

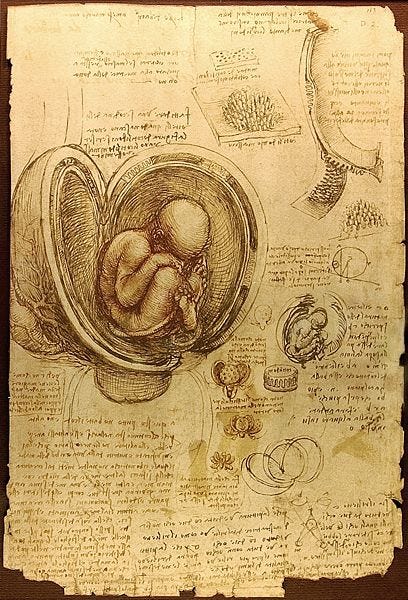

In the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, the practice of rendering the world as images expanded outside the Church. Written text—battle plans, medicinal cures, messages to rulers—added images to help aid in understanding. Leonardo da Vinci is an example of the practice in his anatomical drawings. Illich argues that da Vinci and those who came after him were creating “virtual spaces” with their images, spaces “into which one can’t reach or smell or step or touch.”7 Those diagrams were not “real” in the sense that the human anatomy that da Vinci saw when he opened a cadaver did not truly appear as it did in the drawings. They were an abstraction, a representation of a world that does not exist.

This practice of creating virtual spaces or images to represent the world around us has accelerated over the centuries. For many of us, these abstractions have gone beyond tools to help us understand the world and have instead become the way that we experience the world. Illich speaks to the change this way in 1999:

What impresses me so much is the speed with which, during the second part of my life of 70 years, virtual spaces, images and other objects presented in virtual spaces, have become generalized. There are now quite a few serious thinkers who claim that among the most important, profound changes of the last 25 years is the ubiquity of virtual spaces in which, from which we are asked to derive our knowledge … in which most of the things which we take for granted are shown to us and those which we know are better explained to us—with the idea that only if you have seen it on television is it believable in reality.8

Though Illich did not live to see it, large language models have continued the change he spoke about. These models have taken da Vinci’s act of abstracting the human body into an image and gone to the extreme. Instead of the body, they have abstracted the mind—not just one mind, but the minds of millions. This process of abstraction flattens these minds in the same way images flatten the things they depict, making them one-dimensional and unable to change. They have been turned into a finite set of parameters, including the “weights,” which represent connections between words and ideas in a way a machine can understand, but we as humans cannot. For example, DeepSeek-V3 has 671 billion total parameters and was trained on “14.8 trillion diverse and high-quality tokens.” It can be downloaded to your computer as a set of 163 files of around 4 gigabytes each.

In this, we see the end state of the “corruption of Christianity” that Illich spoke of. The medieval Church’s practice of inscribing the words of the Bible into images has accelerated to the point where those same words are seen as nothing more than “high-quality tokens.” We have gone from icons serving as a threshold to a heavenly reality to screens serving as an interface to a digital reality. ChatGPT is another example of an interface, connecting us to the virtual space in which large language models exist. We’ve traded the insight, wisdom, and awe that can be found in the infinite world of the divine for instant answers sourced from the finite world of the machine.

As I considered this, I was struck by how many of the interactions I have with these models resemble prayers. “Please, help me get my project specification document done,” “please, give me the words to say in this presentation to my bosses,” “please give me wisdom about how to solve this problem.”9 Unlike prayers, the answer is never silence or “no.” Like prayers, the answer isn’t always exactly what I desired. In that case, my prompts become more desperate: “The web site still isn’t doing what I asked you to make it do, please try it again” and “what’s wrong with you, why aren’t you doing what I asked?”10

My “prayers” to ChatGPT show how we approach large language models for their god-like qualities, especially for tasks of creation and tasks of wisdom. When we turn to ChatGPT for help in those areas, we limit ourselves to answers that can be found in its virtual space. While it may have knowledge that can aid in these endeavors, great works of creation and wisdom require knowledge that comes from embodied experience. Large language models have never experienced awe from seeing the beauty of nature or a newborn child. ChatGPT can’t truly know others—friends, parents, grandparents—or be shaped by them. Some argue that these experiences can be embedded into their knowledge, but I find it hard to believe that 671 billion parameters can fully capture the finite world we inhabit, let alone visions of a possible infinite one. Maybe I should find an icon instead.

While I do recommend visiting one yourself, finding one in Western Pennsylvania that was open to visitors on a Friday afternoon was not an easy task. The one I visited was holding its annual Greek Festival at the time, which was the only reason I was able to visit it. The baklava was a nice bonus.

The written transcript for this particular episode is available here. The entire interview behind the series is also available as the book “The Rivers North of the Future” by David Cayley. Chapter 7, “The Gospel and the Gaze” is a fuller version of the transcript above.

Exodus 20:4 KJV

Colossians 1:15 KJV

These are all paraphrases of prompts that I have used personally